Ancient food remains reveal clues into salmon’s distant past

Quick Summary

- Otoliths (ear stones) are hard calcium carbonate structures located behind the brain in fish that acts as a biochronology recorder that can persist for thousands of years.

- Native communities fished along the Feather River, ate salmon and disposed of their carcasses into middens, leaving behind otoliths that were later recovered by archaeologists.

- The age at which the ancient salmon returned to spawn was determined through otolith analysis and compared to modern populations.

- Salmon now return at younger ages and have less age diversity than in the past.

Before the modern era, Chinook salmon in California’s Central Valley lived very different lives. With no industrial-scale ocean fishing and hundreds of extra miles of unobstructed spawning and rearing habitat, these fish may have been able to delay their return to freshwater, grow larger, and produce more offspring. New research published in the Marine Ecology Progress Series by researchers from the UC Santa Cruz, UC Davis Center of Watershed Sciences, Far Western Anthropological Research Group, and NOAA Fisheries in collaboration with Estom Yumeka Maidu Tribe of Enterprise Rancheria, set to put this theory to the test.

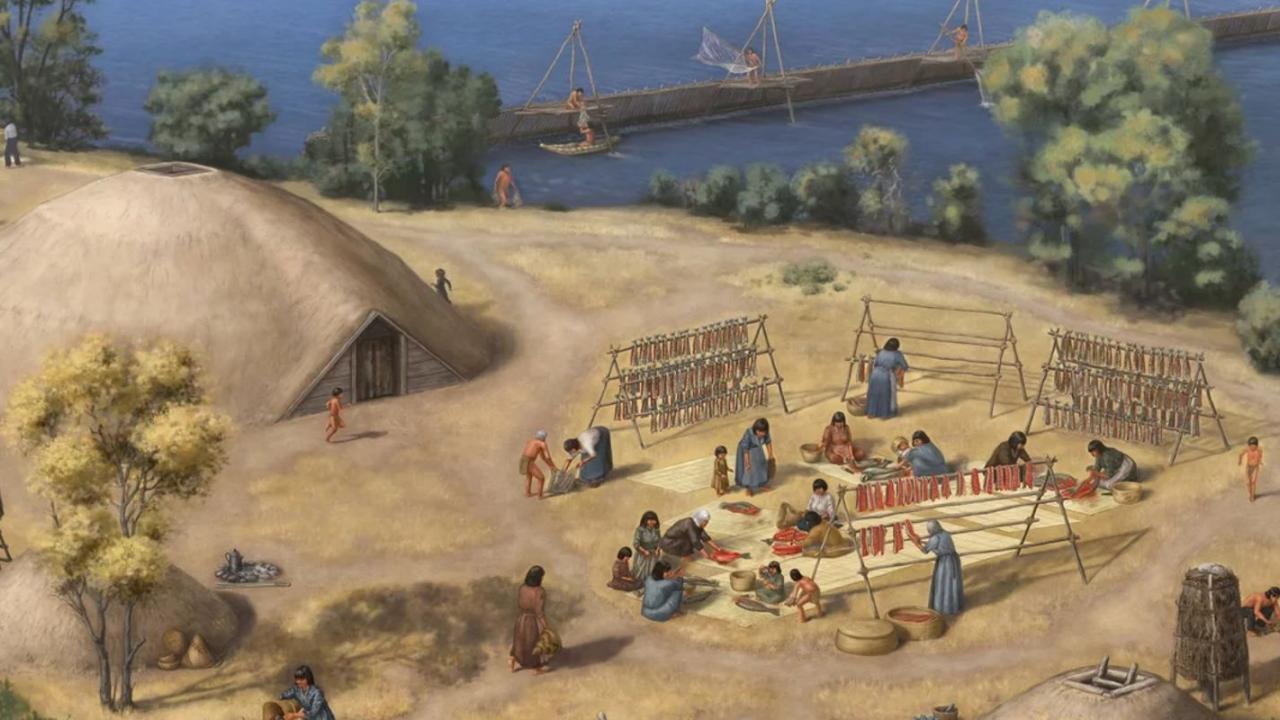

For generations, Maidu communities harvested salmon from the Feather River. They would clean, cook, dry and then store the catch to be eaten throughout the winter months. What remained of the carcasses would be disposed of into waste pits, or middens. Centuries later, archaeologists from the Far Western Anthropological Research Group excavated these middens and were able to document over 6,000 years of Indigenous fishery use. Among a combined collection of over 51,000 bones and other refuse were otoliths, tiny calcium carbonate structures that occur in the inner ear of fish that assist with balance and hearing.

By thin-sectioning and analyzing the unearthed otoliths researchers were able to reconstruct the spawning ages of past salmon populations and compare them to their descendants. This was possible because, much like the rings of a tree, otoliths grow in daily and annual layers, providing a natural record of a fish’s age when it dies.

The results were striking. Compared to their ancestors, modern Central Valley Chinook are younger on average when they return to freshwater to spawn and show less diversity in the range of ages. These findings suggest that modern conditions have imposed strong selection pressures against spending more time in the ocean, outweighing the reproductive advantages of a larger body size. By uncovering how salmon lifespans have shifted over millennia, the study provides a crucial baseline for monitoring future changes in this ecologically and culturally important species.

View the publication: Willmes M., Cordoleani F., Sturrock A.M., Chen E., Satterthwaite W.H., Johnson R.C., Eerkens J.W., Whitman G., Jeffres C., Palkovacs E.P., Ruiz Jr. J.J., Hobbs J.A., Lewis L.S., and Rosenthal J. 2025. Archaeological evidence across four millennia indicates recent erosion of Chinook salmon age structure in California. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 773:149-161 https://doi.org/10.3354/meps14972